5. Vectors¶

Vectors are a crucial part of working with picraft; sufficiently important to demand their own section. This chapter introduces all the major vector operations with simple examples and diagrams illustrating the results.

5.1. Orientation¶

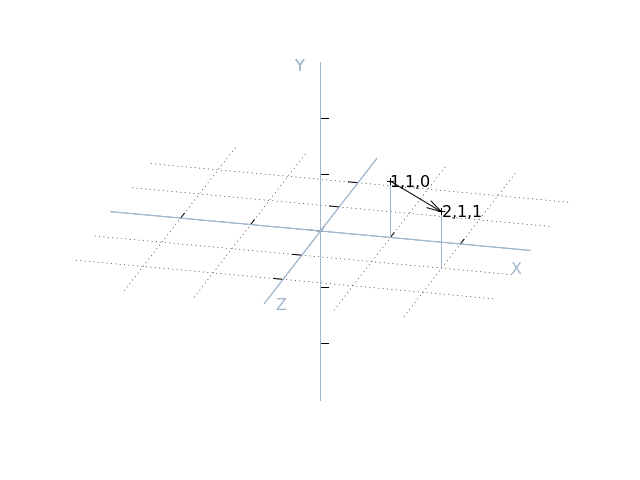

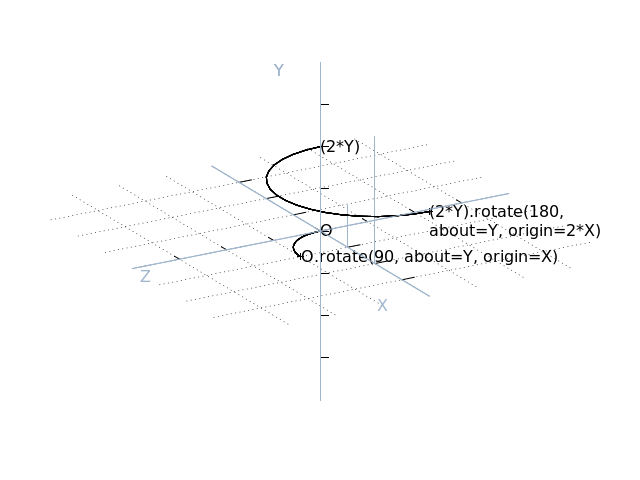

Vectors represent a position or direction within the Minecraft world. The Minecraft world uses a right-hand coordinate system where the Y axis is vertical, and Z represents depth. You can think of positive Z values as pointing “out of” the screen, while negative Z values point “into” the screen.

If you ever have trouble remembering the orientation label the thumb, index finger, and middle finger of your right hand as X, Y, Z respectively. Raise your hand so that Y (the index finger) is pointing up. Now spread your thumb and middle finger so they’re at right angles to each other and your index finger, and you’ll have the correct orientation of Minecraft’s coordinate system.

The following illustration shows the directions of each of the axes:

Positive rotation in Minecraft also follows the right-hand rule. For example, positive rotation about the Y axis proceeds anti-clockwise along the X-Z plane. Again, this is easy to see by applying the rule: make a fist with your right hand, then point the thumb vertically (positive direction along the Y axis). Your other fingers now indicate the positive direction of rotation around that axis.

5.2. Vector-vector operations¶

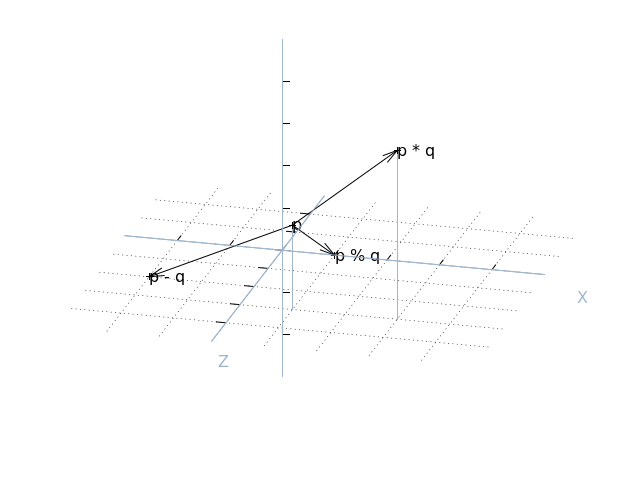

The picraft Vector class is extremely flexible and

supports a wide variety of operations. All Python’s built-in operations

(addition, subtraction, division, multiplication, modulus, absolute, bitwise

operations, etc.) are supported between two vectors, in which case the

operation is performed element-wise. In other words, adding two vectors A

and B produces a new vector with its x attribute set to A.x + B.x,

its y attribute set to A.y + B.y and so on:

>>> from picraft import *

>>> Vector(1, 1, 0) + Vector(1, 0, 1)

Vector(x=2, y=1, z=1)

Likewise for subtraction, multiplication, etc.:

>>> p = Vector(1, 2, 3)

>>> q = Vector(3, 2, 1)

>>> p - q

Vector(x=-2, y=0, z=2)

>>> p * q

Vector(x=3, y=4, z=3)

>>> p % q

Vector(x=1, y=0, z=0)

5.3. Vector-scalar operations¶

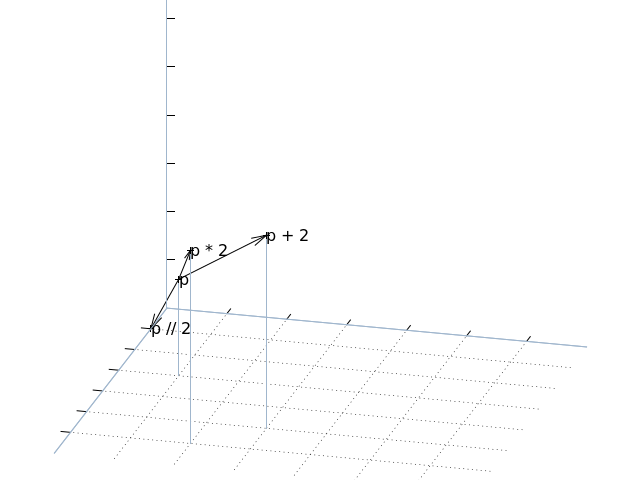

Vectors also support several operations between themselves and a scalar value. In this case the operation with the scalar is applied to each element of the vector. For example, multiplying a vector by the number 2 will return a new vector with every element of the original multiplied by 2:

>>> p * 2

Vector(x=2, y=4, z=6)

>>> p + 2

Vector(x=3, y=4, z=5)

>>> p // 2

Vector(x=0, y=1, z=1)

5.4. Miscellaneous function support¶

Vectors also support several of Python’s built-in functions:

>>> abs(Vector(-1, 0, 1))

Vector(x=1, y=0, z=1)

>>> pow(Vector(1, 2, 3), 2)

Vector(x=1, y=4, z=9)

>>> import math

>>> math.trunc(Vector(1.5, 2.3, 3.7))

Vector(x=1, y=2, z=3)

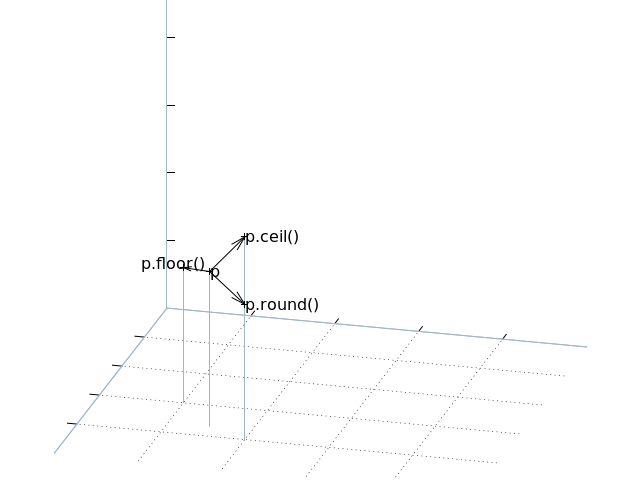

5.5. Vector rounding¶

Some built-in functions can’t be directly supported, in which case equivalently named methods are provided:

>>> p = Vector(1.5, 2.3, 3.7)

>>> p.round()

Vector(x=2, y=2, z=4)

>>> p.ceil()

Vector(x=2, y=3, z=4)

>>> p.floor()

Vector(x=1, y=2, z=3)

Hint

Floor rounding is the method Minecraft uses to convert from a player position to a tile position. Floor rounding may looking simply like truncation, aka “round toward zero”, but becomes different when negative numbers are involved.

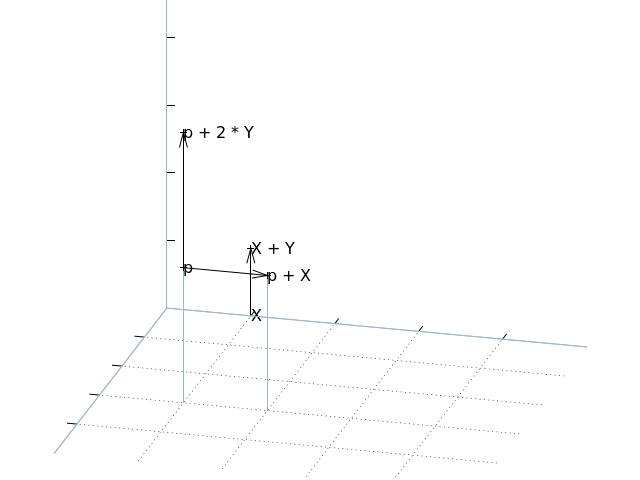

5.6. Short-cuts¶

Several vector short-hands are also provided. One for the unit vector along each of the three axes (X, Y, and Z), one for the origin (O), and finally V which is simply a short-hand for Vector itself. Obviously, these can be used to simplify many vector-related operations:

>>> X

Vector(x=1, y=0, z=0)

>>> X + Y

Vector(x=1, y=1, z=0)

>>> p = V(1, 2, 3)

>>> p + X

Vector(x=2, y=2, z=3)

>>> p + 2 * Y

Vector(x=1, y=6, z=3)

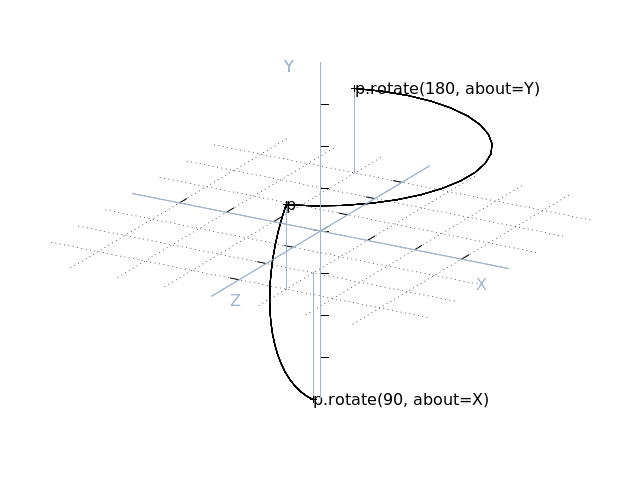

5.7. Rotation¶

From the paragraphs above it should be relatively easy to see how one can

implement vector translation and vector scaling using everyday operations like

addition, subtraction, multiplication and divsion. The third major

transformation usually required of vectors, rotation, is a little harder.

For this, the rotate() method is provided. This

takes two mandatory arguments: the number of degrees to rotate, and a vector

specifying the axis about which to rotate (it is recommended that this is

specified as a keyword argument for code clarity). For example:

>>> p = V(1, 2, 3)

>>> p.rotate(90, about=X)

Vector(x=1.0, y=-3.0, z=2.0)

>>> p.rotate(180, about=Y)

Vector(x=-0.9999999999999997, y=2, z=-3.0)

>>> p.rotate(180, about=Y).round()

Vector(x=-1.0, y=2.0, z=-3.0)

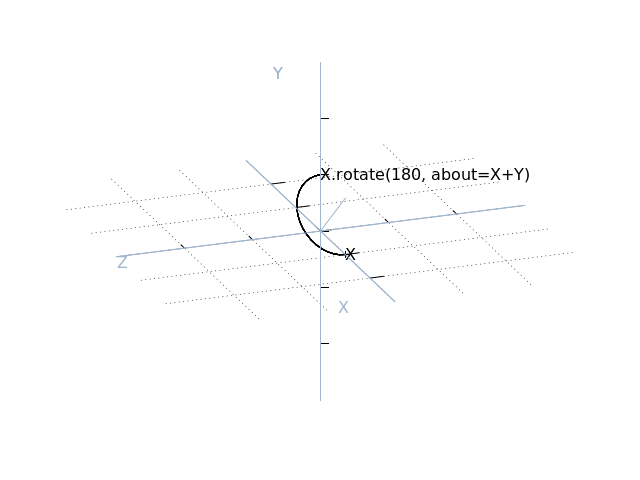

>>> X.rotate(180, about=X + Y).round()

Vector(x=-0.0, y=1.0, z=-0.0)

A third optional argument to rotate, origin, permits rotation about an arbitrary line. When specified, the axis of rotation passes through the point specified by origin and runs in the direction of the axis specified by about. Naturally, origin defaults to the origin (0, 0, 0):

>>> (2 * Y).rotate(180, about=Y, origin=2 * X).round()

Vector(x=4.0, y=2.0, z=0.0)

>>> O.rotate(90, about=Y, origin=X).round()

Vector(x=1.0, y=0.0, z=1.0)

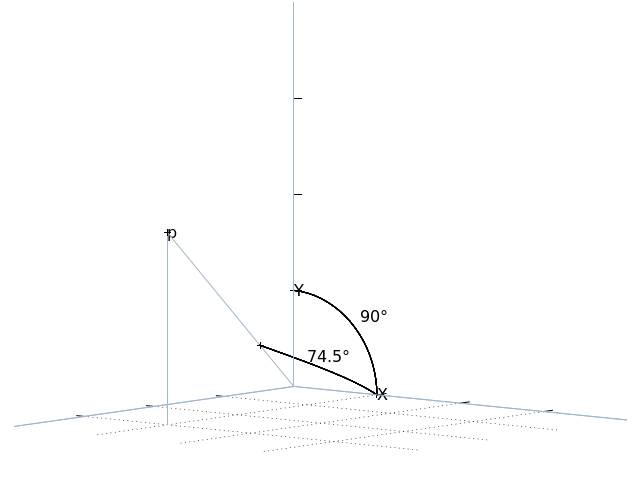

To aid in certain kinds of rotation, the

angle_between() method can be used to determine

the angle between two vectors (in the plane common to both):

>>> X.angle_between(Y)

90.0

>>> p = V(1, 2, 3)

>>> X.angle_between(p)

74.498640433063

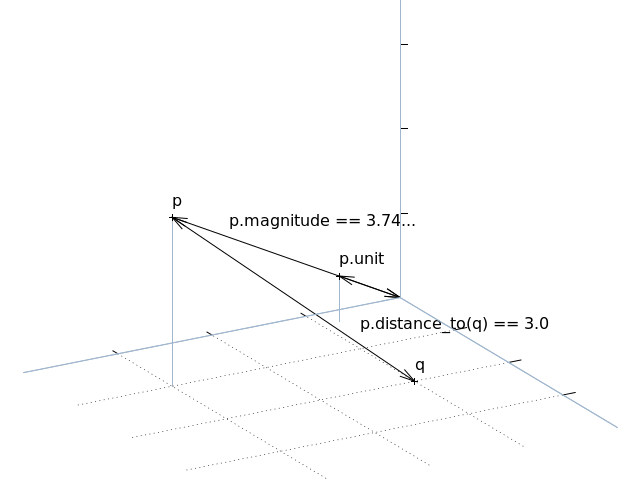

5.8. Magnitudes¶

The magnitude attribute can be used to determine

the length of a vector (via Pythagoras’ theorem), while the

unit attribute can be used to obtain a vector in

the same direction with a magnitude (length) of 1.0. The

distance_to() method can also be used to calculate

the distance between two vectors (this is simply equivalent to the magnitude of

the vector obtained by subtracting one vector from the other):

>>> p = V(1, 2, 3)

>>> p.magnitude

3.7416573867739413

>>> p.unit

Vector(x=0.2672612419124244, y=0.5345224838248488, z=0.8017837257372732)

>>> p.unit.magnitude

1.0

>>> q = V(2, 0, 1)

>>> p.distance_to(q)

3.0

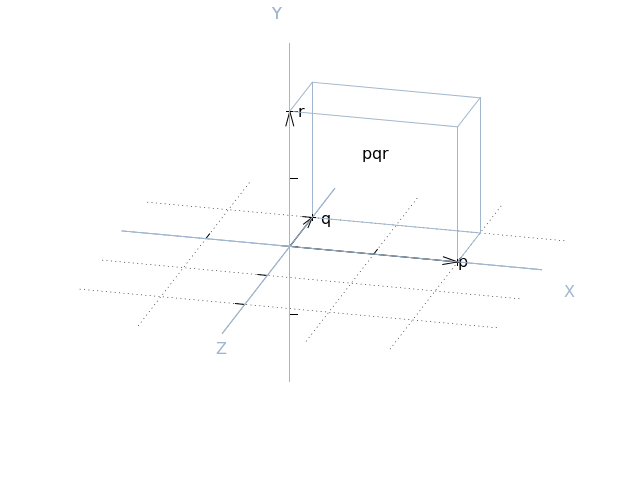

5.9. Dot and cross products¶

The dot and cross products of a vector with another can be calculated

using the dot() and

cross() methods respectively. These are useful for

determining whether vectors are orthogonal (the dot product of orthogonal

vectors is always 0), for finding a vector perpendicular to the plane of two

vectors (via the cross product), or for finding the volume of a parallelepiped

defined by three vectors, via the triple product:

>>> p = V(x=2)

>>> q = V(z=-1)

>>> p.dot(q)

0

>>> r = p.cross(q)

>>> r

Vector(x=0, y=2, z=0)

>>> area_of_pqr = p.cross(q).dot(r)

>>> area_of_pqr

4

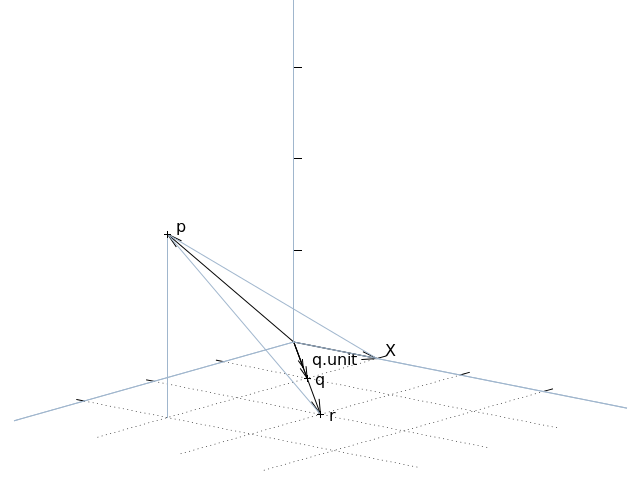

5.10. Projection¶

The final method provided by the Vector class is

project() which implements scalar projection.

You might think of this as calculating the length of the shadow one vector

casts upon another. Or, put another way, this is the length of one vector

in the direction of another (unit) vector:

>>> p = V(1, 2, 3)

>>> p.project(X)

1.0

>>> q = X + Z

>>> p.project(q)

2.82842712474619

>>> r = q.unit * p.project(q)

>>> r.round(4)

Vector(x=2.0, y=0.0, z=2.0)

5.11. Immutability¶

Vectors in picraft (in contrast to the Vec3 class in mcpi) are immutable. This simply means that you cannot change the X, Y, or Z coordinate of an existing vector:

>>> v = Vector(1, 2, 3)

>>> v.x += 1

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: can't set attribute

>>> v.x = 2

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: can't set attribute

Given that nearly every standard operation can be applied to the vector itself, this isn’t a huge imposition:

>>> v + X

Vector(x=2, y=2, z=3)

>>> v += X

>>> v

Vector(x=2, y=2, z=3)

Nevertheless, it may seem like an arbitrary restriction. However, it conveys an

extremely important capability in Python: only immutable objects may be keys of

a dict or members of a set. Hence, in picraft, a dict can be

used to represent the state of a portion of the world by mapping vectors to

block types, and set operators can be used to trivially determine regions.

For example, consider two vector ranges. We can convert them to sets and use the standard set operators to determine all vectors that occur in both ranges, and in one but not the other:

>>> vr1 = vector_range(O, V(5, 0, 5) + 1)

>>> vr1 = vector_range(O, V(2, 0, 5) + 1)

>>> vr2 = vector_range(O, V(5, 0, 2) + 1)

>>> set(vr1) & set(vr2)

set([Vector(x=0, y=0, z=2), Vector(x=1, y=0, z=0), Vector(x=2, y=0, z=2),

Vector(x=0, y=0, z=1), Vector(x=1, y=0, z=1), Vector(x=0, y=0, z=0),

Vector(x=2, y=0, z=1), Vector(x=1, y=0, z=2), Vector(x=2, y=0, z=0)])

>>> set(vr1) - set(vr2)

set([Vector(x=1, y=0, z=3), Vector(x=1, y=0, z=4), Vector(x=2, y=0, z=4),

Vector(x=1, y=0, z=5), Vector(x=0, y=0, z=5), Vector(x=0, y=0, z=4),

Vector(x=2, y=0, z=3), Vector(x=2, y=0, z=5), Vector(x=0, y=0, z=3)])

We could use a dict to store the state of the world for one of the ranges:

>>> d = {v: b for (v, b) in zip(vr1, world.blocks[vr1])}

We can then manipulate this using dict comprehensions. For example, to modify the dict to shift all vectors right by two blocks:

>>> d = {v + 2*X: b for (v, b) in d.items()}

Or to rotate the vectors by 45 degrees about the Y axis:

>>> d = {v.rotate(45, about=Y).round(): b for (v, b) in d.items()}

It is also worth noting to that due to their nature, sets and dicts automatically eliminate duplicated coordinates. This can be useful for efficiency, but in some cases (such as the rotation above), can be something to watch out for.